Artigo escrito pelo juiz federal Renato Becho, ao ITR.

Brazilian Federal Judge Renato Becho discusses the improper use of the Usitecno case as an example of how the country’s judicial system is failing to uphold the rule of law without influence

By Renato Becho

Brazil is ranked 58th in the Rule of Law Index by the World Justice Project (WJP), which does not appear to be a good position for one of the world’s largest economies. What is happening in Brazil’s legal system that it deserves such an evaluation? This article illustrates, through tax law, the situation by presenting a pivotal judicial case. In that case, the tendency to avoid applying the law is exposed.

Anyone visiting Brazil can see how rules are disregarded. Brazilians frequently cross streets without using the pedestrian crossings, people from Rio de Janeiro “do not like red lights” – a well-known phrase, and it is common to see motorcycles in São Paulo where the driver rides on the sidewalk, even though the Traffic Code prohibits this.

However, when the World Justice Project ranked Brazil as 58th among 126 countries in the Rule of Law Index, it was probably thinking about much more than just the Traffic Code. In the same index, some of Brazil’s neighbours occupy much better positions. For example, Uruguay, Chile, and Argentina respectively rank 23rd, 24th, and 46th.

On the other hand, Brazil’s ranking is particularly problematic when it is considered that in 2012 it temporarily overtook the UK as the sixth largest economy. In 2017, it was considered the world’s eighth largest economy by nominal GDP and eighth largest by purchasing power parity. When comparing legal and economic data in this way, it seems that Brazil’s economy is, at least up to this point, more robust than its law.

Confusing statute of limitations in tax proceedings

Article 174 of National Tax Code (CTN) provides for a five-year statute of limitations, where the tax authorities can open a claim for any possible outstanding amounts of tax.

Article 219 of Civil Procedure Code (CPC/1973) regulates the service of process and its effects. Once a taxpayer is issued a notice of the tax claim through a summons and the evidence of this notice (known as the ‘service of process’) is included in the legal case file, the action is considered as being filed. This triggers the beginning of the five-year statute of limitations period. However, some conditions must be met:

- The interruption of the limitation period runs from the day on which the action was filed;

- The claimant (tax authority) needs to carry out the service of process within 10 days after the judge has ordered it. The claimant will not be liable for any delay caused by the judiciary service;

- If the defendant is not served with the process within 10 days of the notice being issued, the judge must postpone the due date by 90 days; and

- If the process is not served within the period of 100 days, the interruption of the limitation period will not be deemed to have begun on the day on which the action was filed.

It is important to highlight how long a judicial order to serve a process takes to be carried out. Apart from provisions in the CPC, there is no rule addressing the issue. In one case, it took almost 20 years, where the tax enforcement was filed on May 25 1976 and was served to the taxpayer on October 25 1994 (Debitor’s Petition to Challenge on Tax Enforcement No. 95.0504593-0, São Paulo.)

The interruption of the period for the statute of limitations is the object of hundreds of thousands of appeals to many courts all over Brazil. It is a good example as to why the legal system needs to be changed to confer some stability in judicial decisions. A relevant case shows why.

The Usitecno case

The Usitecno case, presented by Justice Luiz Fux, is a special appeal (No. 1.120.295/SP) to the Superior Court of Justice (STJ), which is the third instance court, just below the Supreme Court. The main point decided in the case concerned the time when the statute of limitations in the tax enforcement matter was interrupted, despite the statute of limitations not being contested by either the claimant or defendant in this case. They were contesting an article from the National Tax Code (CTN).

Justice Fux did not apply the CTN or the four conditions of the CPC mentioned above. He chose to apply only the first condition mentioned. He said the limitation period started from the date the case was allocated to the court against the inaction of the Attorney for Public Finance. He suggested that the Tax Code is incoherent and applied just a part of the CPC provision. All of the other Justices voted in agreement with Justice Fux.

The decision reversed countless other cases where the limitation period was determined correctly. The Usitecno case represents a strong precedent that has been applied many times in cases before the STJ and other courts.

According to the rule of law, Congress, not the Judiciary, must approve rules that change the start date of a limitation period through supplementary law. A change of this magnitude should not have occurred through a judicial decision.

The conflict between the Usitecno and Coprin cases

Although the Usitecno case has set a precedent, it directly conflicts with another case that was ruled upon a few months later.

The First Section (an ordinary panel) of the STJ adjudicated in the Usitecno case in May 2010. Just 10 months later, the Special Body of the STJ, a higher panel than the First Section, decided the Coprin case. In this case, the STJ decided that the National Tax Code (CTN) must be applied to interrupt the period for the statute of limitations in tax enforcement matters.

In other worlds, the rule of law on which the judicial decision in the Coprin case was decided upon stated that a supplementary law must determine the period for the statute of limitations in tax law. In the Usitecno case, the STJ applied only half of an article of the CPC, an ordinary law. Therefore, the Coprin case overruled Usitecno – a case in which the STJ had departed from the CTN (a supplementary law) in the same situation.

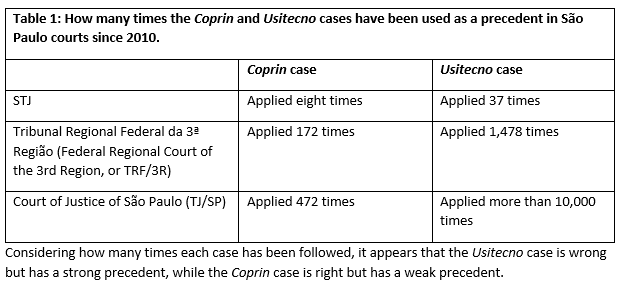

In light of the Coprin case, it would be assumed that the Usitecno case would no longer be followed. However, analysing the websites of the STJ, the Federal Court in São Paulo and the State Court in the same capital shows the opposite (see Table 1).

Insufficient reaction

The Civil Procedure Code of 2015 introduced a system of binding judicial precedents in Brazil. So, why do so many judges adhere to a per incuriam decision? In other words, why can some cases be characterised have having little regard to the rule of law or facts of a case? Debates about legal realism can help.

Hans Kelsen, the most influential jurist in Brazil, proposes a “theory of positive law”, doing “a science of law (jurisprudence), not legal politics”. He has criticised the science of law for mixing elements of psychology, sociology, ethics, and political theory. Kelsen presented a norm “as a scheme of interpretation”, and to him norm “is the meaning of an act by which a certain behaviour is commanded, permitted, or authorised”. It is possible to label it as legal formalism: judges and justices ought to apply only acts and statutes with no extraneous elements.

Former US Chief Judge of the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals Richard Posner, however, discusses legal realism, a school of thought in which other circumstances affect judicial rules. Alex Kozinski, former chief judge of the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, criticised legal realism in a conference for judges, remembering the caricaturised discussion about what judges ate for breakfast. He thinks that external influences are undesirable. However, there is some interesting research done by Professors Shai Danziger and Jonathan Levav, as well as graduate student Loira Avnaim-Pesso indicating the opposite. They concluded that “judicial rulings can be swayed by extraneous variables that should have no bearing on legal decisions”, including breaks to eat.

The influences of breakfast

Brazil adheres to the civil law tradition with a legal Constitution and numerous codes and acts. In spite of the Constitution and the characteristics of the system, the system is not working well.

Government agencies, civil servants, attorneys, prosecutors, judges and justices do not apply the Constitution and the laws all the time. The Usitecno case shows this to be so, constituting a relevant example of a per incuriam decision, in which the courts have disregarded the legal system to indulge public finances instead of applying the law in favour of taxpayers and according to the rule of law. In spite of the fact that the case has been overruled by another decision from a higher adjudicating body, courts have continuously followed the Usitecno case.

The CPC/2015 imported from the common law theory of precedents in an attempt to confer stability to judicial decisions and legal security to society. However, if judges and justices do not apply the law all the time, merely changing a code will not be enough.

Regarding the debate between legal formalism and realism, it is possible to identify that some non-legal elements are influencing Brazilian judges and justices. Although what judges eat for breakfast may be irrelevant, what they read in the newspapers during breakfast (corruption, fiscal risks, less adherence to the law by some taxpayers) could interfere in their decisions. Brazilian universities must start the study of legal realism, in a way to comprehend the judges' decisions based on elements other than the statutes and codes.

The judiciary reduces adherence to the rule of law to comply with the government and against the taxpayer. Losing confidence in the government severely impacts the Brazilian economy. After all, business needs legal certainty.

This article was written for ITR. The views expressed in this article are the personal views of Judge Renato Becho.